When it comes to enjoy scotch and “tasting” it, many of your senses come into play. You can see the color of the scotch, you smell the aromatics as you swirl it in your glass, you taste the flavors that awaken you as you sip it, and then comes the finish… the warmth and in your throat and the aftertaste that lingers in your mouth. Combined, the aromatics, the flavor, the heat, the mouthfeel, they all contribute to the act of “tasting” scotch.

One of the most important things about tasting is to become familiar with the flavors themselves. How can you understand what tastes “peaty” if you don’t know what “peaty” is? It’s like a child who has never tasted coconut, there is no way they can pull out that flavor from a rum cake, right? The best way to build your sense of flavors is to get a feeling for what each flavor is independently so that you can figure out what it is when you combine them either other flavors.

Let’s get to the senses…

The Eye

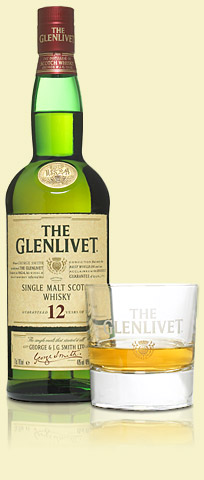

The first way yo always interact with scotch is by looking at it, right? Scotches aged for a short period in oak casks will look very light golden in color. As they are more or are introduced to rum casks or sherry casks, the color becomes a darker amber. In general, a light colored scotch will be light in flavor and a dark scotch will often have more flavor complexity.

The Nose

The first part of tasting scotch involves your nose and detecting the scents that leave the scotch. As I sniff more and more scotch, I’m getting better at detecting the various aromatics that leave the glass. Peatiness is likely the easiest to detect but there are other flavors as well like fruitiness, grass, heather, salt, sherry, spiciness, etc. Much like flavor, it will be like a symphony in which you will try to identify individual notes.

The Mouth

Your mouth is how you will get the three other components in tasting – body, palate, and finish. Body refers to how full the scotch feels. Some will feel light, others will have a weightier feel to them. As you drink more, you’ll be able to see how the body of each scotch differs and be able to figure out what is considered “light” and what is considered “full.” Body is also often called mouthfeel.

Palate refers to the flavors you taste and, as Michael Jackson has noted in many of his books, an experienced taster will have to return frequently to a scotch, over several days, to get a full sense of its flavors. As I said before in the Nose, it’s like a symphony. You know there are a lot of instruments but it takes a lot of time to identify them correctly.

Finish refers to the after-taste and more. After you swallow, there will be a lingering flavor that joins the warmth of the scotch going down your throat. It’s this flavor, along with the warmth, that finish refers to. When I began tasting scotch, all the finishes tasted similar (not the same, but similar) but as I enjoyed more varieties I discovered each ended differently and in complement with the other tasting aspects. Some ended more sharply than others, some had some spiciness, and others simply warmed the body like a warm blanket by the fire.

The one thing to take away from this isn’t that you should try to identify everything or try to know everything, just try to figure out one new thing per sip (or couple of sips). Think of a bottle as a novel, you learn one new thing each time you turn the page, and you’ll be able to enjoy it for a long time (and isn’t that what it’s all about?).